Let’s dive

in the modern history of Manduria and discover how stories of collaboration

between peoples of different language and culture can arise. Let’s visit the

Civic Museum of Manduria.

I’ve

already talked to you about Manduria on this blog: I guided you along the

streets of its old town centre, we dived in its history to meet the Messapians,

we tasted its wine loved in the world, I showed you the beauty of its sea and its natural wonders.

Today I’m talking to you again about the town of Primitivo wine to guide you in another place that keeps the memory of the people of Manduria. Let’s discover together the Civic Museum of Manduria dedicated to the Second World War.

Don’t let

the introduction scare you. It’s true , we’re talking about a horrible period

and each year we remember its atrocity, but the Civic Museum of Manduria wants

to tell something that usually is left out in favour of historical facts: here

we talk about the life of the people of Manduria and, in particular, about

their relationship with the American aviators who had been based in this area

for 14 months, between 1943 and 1945. The Museum tells the human side of that

period.

The creation of the Civic Museum

Its name is

Museum of the Second World War, but it also hosts witnesses dating back the

Great War, especially, as we’ll see further, referring to the warm hospitality

that characterizes the people of Manduria.

The visit of the Civic Museum of Manduria

Let’s enter

Palazzo delle Servite, a noble palace dating the 18th century in the old town

centre. We coast the refined cloister, with an elegant well in the middle, and

go upstairs on the first floor. After a brief staircase, here we are in the

Civic Museum.

Four large

paintings realized by the creativity of the students of art high school,

inspired by some photographs of that time, welcome and guide us toward the

museum itinerary of memory. In a large room, several showcases, which collect many items, are neatly organized. From the

door, we can already see military uniforms and photographs from long ago.

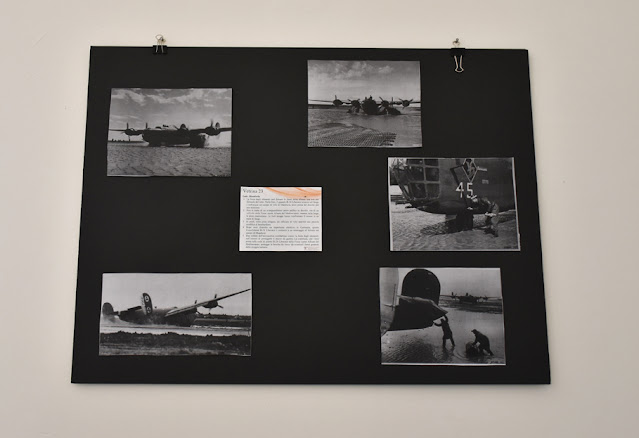

Men

captured in photo while trying not to get bogged down tell how the Americans of the 450th

Bomb Group arrived to Lake Manduria. It

makes smile that the muddy area formed in December because of stagnation was

defined “lake”.

Anyway,

that was enough for the Americans to roll up their sleeves in order not to make

the planes get bogged in muddy soil. Memories start to materialize in the items

around us.

Pierced

steel planking: we see them in the hands of the soldiers to prevent trucks and

planes sink in mud; we turn our heads and see them on the wall, directly from

the 40s of last century, as they’ve travelled in time.

There also

are specific military elements, as the precision pointer used by bombardiers.

Some items are there to remember the period that, with this exhibition, we’re going

through, in case we got distracted and forgot which years we’re talking about,

thanks to the humanistic story set in the museum.

Manduria, like a large part of Puglia, didn’t perceive directly the horror of war; they

rather suffered the hunger that came from it. With the arrival of the Americans,

some activities had to adapt to the needs of the war, like the propagandistic

one, the informative one, but also the entertaining one. We’re always talking

about men, boys, who found themselves fighting a war.

As we’re

talking about men, here that some colour notes emerge and tell about these

people, about their life in Manduria and about the way the people of Manduria

adapted themselves to the Americans and to the situation.

The

information that come to us were documented by the press of that period, in

particular by the weekly magazine The Bomb Blast: it was written in American

English and reported news of any kind. One of them was the announcement of the

opening of a laundry, where they stressed the guarantee of hygiene. Now we take

it for granted, but in Puglia of the 40s hygienic conditions weren’t those

we’re used nowadays.

They also

found a warning for American aviators: they absolutely had to beware of the

Purple Death. What was it? Well, we’re in Manduria, the town of Primitivo wine:

the Purple Death actually was the wine, or better to say the effects caused by

it.

Primitivo

is a quite strong wine, whose alcohol content is about 18%. If you’re not used

to it, it goes down wonderfully, but equally softly leads you in the arms of

Bacchus. So, aviators, who had to drive trucks and planes, had to be careful

with wine, because the risk of serious accident was real.

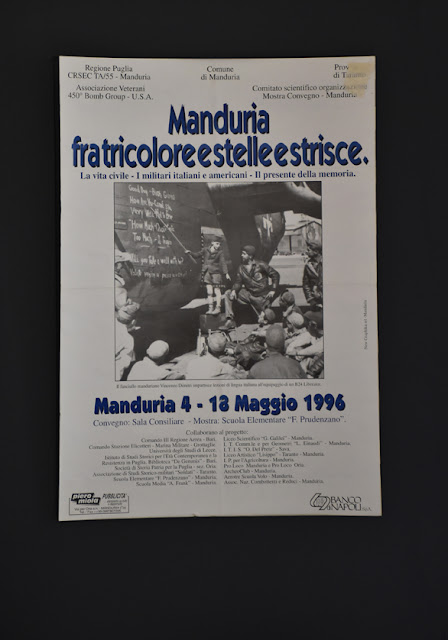

Let’s

continue and see a poster with an interesting photograph: a boy, standing on a

stool, who teaches Italian to the Americans. It’s a beautiful witness of the

collaboration between peoples of different language and culture, despite the

circumstances that brought them together.

We get

closer to read the sentences the boy is teaching and soldiers are so interested in learning:

Buongiorno, come state? (Good morning, how are you?), Vorreste passeggiare

con me? (Would you like to go for a walk with me?) and we can’t hold a

mischievous smile. Surely, those were useful sentences and, apparently, also

efficient, as we know that there had been several marriages between the Americans

and the women of Manduria!

When the Americans

left Manduria, they also left many objects. Besides pierced steel planking,

they found several bomb holders, tin boxes and even trucks. The people of

Manduria collected that stuff and reused it: pierced steel planking became

excellent gates; bomb holder were used as stools or readapt in creative ways to

face everyday life needs. So, the people of Manduria gave free rein to their

innate creativity to turn those “wastes” to their advantage.

The Heroes of Manduria

A big showcase

is dedicated to two heroes of Manduria. According to their lives, they honoured

the town and brought a witness of that period: they are Cosimo Moccia and Elisa

Springer.

Cosimo

Moccia was a carabiniere decorated with Gold Metal of Military Valor for having

chosen death with his companions, war prisoners, rather than betray his country

and reveal the names and the hiding places of partisans who he had joined.

The letters

shown on the totem define his profile as a man, with his hopes and his desire

of coming back home to his family. Nothing in those texts let foresee what then

would have really happened.

Next to it, the

showcase dedicated to Elisa Springer tells the story of this Jewish woman, born in

Vienna, but grown up in Manduria, survived to holocaust. After many years of

silence, she decided to dedicate her life to the witness of what she had lived,

in order to make know the horrors she had to suffer, with the hope that

knowledge can prevent them happening again.

A wall

covered with photographs shows the faces of posed young men. They’re the sons

of Manduria, who lost their life during the Second World War; some of them are

the victims of Shoha and sinkholes. It’s a way to give them dignity and to

thank them for their sacrifice. They’re here with their stories and bring their

witness.

The Photographic exhibition about the First World War

We leave

the room dedicated to the Second World War to walk through the corridor that

hosts a photographic exhibition. It tells about the hospitality in Manduria

received by the refugees of Trentino during the Great War.

As already

said, the essential element of this museum is humanity and the sense of sharing

between people who don’t know each other and sometimes don’t even understand

each other (because the people of Trentino spoke German and those of Manduria

local dialect).

From

documents we see that people of Trentino loved Apulian “exotic fruit”:

zucchini, tomatoes, eggplant, figs and Indian figs. We listen to this and smile

thinking that today we can find at home products from any place in the world.

Also in

this period we find a symbolic figure: he’s Mandurino Weiss. He was born in

Manduria in 1916 and his parents were from Trentino, welcomed in town. His

father, to thank the people of Manduria for their warm hospitality, named him

Mandurino. The day when he went to the registry office to record his son, a man

of Manduria, Michele Dinoi, listening to his motivation, decided to name his

son Trento Giovanni, to thank that man for his act.

The two

children grew up and, during the Second World War, enlisted and went to

Ethiopia. The two didn’t know each other personally, but they heard about their respective stories. At the moment of appeal, after both having been captured by

the British, they recognised each other and found themselves again.

Our journey

in the modern history of Manduria ends here. Even if it might seem strange, at

the end of the exhibition you feel a bit closer to Manduria and its community,

as if we really have met those people and they personally told us their own

story.

Thanks to

the cooperative Spirito Salentino and to the group Cuore messapico, together

with Anna and Angela, who hosted and guided us through the memories of the town

and who animate the museum with events and activities addressed to young and

old.

For further

information about the museum, you can visit the website of the Civic Museum of Manduria.

Commenti

Posta un commento

Feel free to leave a comment!

I would be glad to know your opinion! ;)

Thank you! :)